Iran is by origin the same word as Aryan, and throughout history has been intermittently applied to the people of Indo-European, that is, Aryan origin occupying the plateau and to the plateau itself.

Today Iran is a triangle set between two depressions - the Caspian Sea to the north and the Persian Gulf to the south. It is bounded on the north by Armenia, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan and the Caspian Sea, on the east by Afghanistan and Pakistan, on the south by the Persian Gulf and the Sea of Oman, and on the west by Iraq and Turkey.

The triangle of the Iranian Plateau is bounded by mountains rising round a central depression, a desert region formed by the bed of a dried-up ocean. The western mountains, or Zagros range, run from north-west to south-east, and the northern part of the triangle is formed by the, mighty Alborz range; skirting the southern shore of the Caspian Sea, it forms a high and narrow barrier which separates the coastal area with its luxuriant vegetation from the desert regions of the interior.

In the country fringing the Alborz and Zagros ranges and in certain mountain valleys conditions for life are more favorable, owing to the better water-supply and to the fertile soil. On the higher mountains the snow falls in winter, building up a reserve of moisture for the dry summer months; there are also winter and spring rains. All the larger centers of population and the majority of the smaller ones are situated near or in the mountains because of the more abundant supplies of water that are available. These two chains, which meet in the north-west, serve as buttresses for the central plateau, a relatively arid region which varies in altitude from over 6,000 to under 2,000 feet. On this plateau the rainfall is relatively sparse, and in the lower-lying regions the soil is very saline, making cultivation, and therefore life, impossible, except in the few oases such as that of Tabas.

Two great deserts, the Dasht-e Lut and the Dasht-e Kavir, occupy a large part of the central plateau and together account for one half of the desert area and one sixth of the total area of Iran. These two deserts are often pock-marked with the round air-holes of Qanats, underground channels which connect the water-table. with farms and villages. They are anything up to thirty miles long, and may entail the digging of a shaft several hundred feet deep, and have been a unique Persian specialty for many centuries, and form a prodigiously complex system of water distribution.

Tehran - the capital of Iran - is located at the foothills of the Alborz mountains; the city's relatively temperate climate was the principal attraction for the Qajar monarchs. There are several royal palaces including the Sahebqaraniyeh palaces in northern Tehran, and the Golestan and Marmar (Marble) palaces in southern Tehran, now turned into museums. The Shams-ol Emareh and the Imam Mosque (formerly "Royal Mosque" or "Masjid-e Shah"), are both near the bazaar (the commercial center).

The Alborz range covers the entire Caspian coast stretching from Khorassan in the east to northwestern Iran. Three roads lead to the Caspian provinces from Tehran, namely the Chalus, Haraz and Firuz Kuh roads. The Chalus road is the most scenic route, winding its way through towns and villages towards the southern tip of the Caspian Sea. People living in these towns still wear their traditional costumes and speak their traditional dialects. A short drive from Chalus will lead to Kelardasht, one of the most attractive areas the traveler will cross on this road. Traveling inland past the provincial capital Rasht and the town of Fuman, we arrive at the growing but well -preserved village of Masouleh. The mountainside village has been declared a UNESCO World Heritage Sight, undoubtedly for its rare architecture, where houses dominate each other. As well as growing rice, the staple food product of the area, Gilan specializes in the production of tea.

The Alborz range covers the entire Caspian coast stretching from Khorassan in the east to northwestern Iran. Three roads lead to the Caspian provinces from Tehran, namely the Chalus, Haraz and Firuz Kuh roads. The Chalus road is the most scenic route, winding its way through towns and villages towards the southern tip of the Caspian Sea. People living in these towns still wear their traditional costumes and speak their traditional dialects. A short drive from Chalus will lead to Kelardasht, one of the most attractive areas the traveler will cross on this road. Traveling inland past the provincial capital Rasht and the town of Fuman, we arrive at the growing but well -preserved village of Masouleh. The mountainside village has been declared a UNESCO World Heritage Sight, undoubtedly for its rare architecture, where houses dominate each other. As well as growing rice, the staple food product of the area, Gilan specializes in the production of tea.

At its western end, the Alborz Range reaches Iranian Azerbaijan in the center of which lies the salt lake of

Orumiyeh. This is a densely populated region, and in its fertile valleys, wheat, cotton, rice and tobacco are cultivated. It's capital is Tabriz. The heart of the city beats in the busy alleyways and stalls of the main bazaar, which the sun struggles to illuminate through openings in the ceiling. Tabriz position in an earthquake zone and its historical vulnerability to repeated Ottoman attacks have left the city with few historical monuments of note. One of these is the 15th century 'Blue Mosque' built under the local Qara Qoyounlu rulers. Of further interest to visitors is the 11 Goli pavilion, a 19th century structure built in the middle of a lake near Tabriz.

The visible remains of the ancient city of "Rey" are on the eastern fringe of Tehran. The site, at the outlet of an abundant underground layer of water, was occupied in the Neolithic Period. Excavations of the mound of Cheshmeh Ali have yielded pottery dating from the 5th millennium B.C. The best-preserved building in Rey is the so-called Tower of Toghrol Beig, a Seljuk funerary tower dated 113 9-1140.

The town of Saveh, 140 km. from Tehran, was a flourishing center with a number of libraries during the Islamic period, until destroyed by the Mongols in the 13th century. Today its large enclosed gardens and orchards (baghs) provide a variety of fruit, especially pomegranates that are greatly appreciated., Leave Tehran by the west, we reach Qazvin, a historical city founded by Sassanian king, Shapur 1. The chief things of interest in Qazvin are some fairly well preserved buildings such as Sabz-e Maidan, the pavilion of Ali Qapu, the Jame' Mosque (Masjid-e Joni-eh).

The city of Hamadan lies at the foot of the Alvand mountain. Its foundation has been attributed to the Assyrian queen Semiramis who ruled in the loth Century B.C. The modem city is built on the remains of the ancient Ecbatana (or Hegmatana) or Place of Assembly, capital of the Medes in the 7th and 6th centuries B.C. The town continued to expand and flourish under the Achaemenian and Parthian. Its importance is further confirmed by a large Achaemenian inscription known as Ganjnameh and a large stone lion. Due to the presence of the Mausoleum of Biblical Queen, who married the Achaemenian kings Artaxerxes 1 (486-465 B.C.) and her foster father Easter Mordecai, the city is a popular place of pilgrimage for Iranian Jews. The medieval philosopher and physician Ibn-e Sina, or Avecina, whose writings were studied in Europe until the 19th century, rests here. Other monumental places of the city are the Alavian Tomb, the Mausoleum of Baba Taher (the Iranian poet), and the Ali Sadr cave.

The provincial capital of Kermanshah is an important agricultural center in western Iran, and was famous in ancient times for its superb breed of horses and excellent vineyards. It is also the land of the Kurds, a proud people who maintain their own language and colorful mode of dress. The relief of Darius'§ victory over rebels at Bisotun near the town of Kermanshah and at Taq-e Bostan, a number of relieves have been carved out of the mountainside, and covered by a vault. Outside, QaJar kings have also been depicted enthroned, in the style of their Sassanian forbears. The Tekiyeh-e Mo'avenol-ol Molk is one of Kerman shah's religious sites, providing a beautiful example of QaJar (19th century) painting and tile-work.

The southern part of the Zagros is called Lorestan. On the slopes of the now denuded mountains once stood green forests of oak, while lower down in the valleys wheat and barley are brown. Because of the heat and drought in the plains, horses and cattle must be driven to the higher pastures of Lorestan in the summer. As a result one part of the population leads a semi nomadic existence which is quite different from that of the people settled in the towns. Part of the Mesopotamian plain to the south-west of the Zagros ranges is called Khuzestan. The frontier runs by the Shatt-ol Arab which is formed by the junction of the Tigris and the Euphrates. Thanks to the extensive irrigation, not only cereals, but more profitable crops such as cotton, rice and sugar-cane now are grown there on a large scale. Ahvaz the capital of Khuzestan, is situated in the heart of the plain and is extremely hot most of the year. The town of Shushtar is on the right bank of the river Gargar, flanked by Dezful in the west, and by Ahvaz and the Qir Dam in the south. Shuslitar was an important site under the Parthian and Sassanian, as confirmed by the considerable number of bridges and fire temples remaining. The town's ancient water mills are among its attractions.

The southern part of the Zagros is called Lorestan. On the slopes of the now denuded mountains once stood green forests of oak, while lower down in the valleys wheat and barley are brown. Because of the heat and drought in the plains, horses and cattle must be driven to the higher pastures of Lorestan in the summer. As a result one part of the population leads a semi nomadic existence which is quite different from that of the people settled in the towns. Part of the Mesopotamian plain to the south-west of the Zagros ranges is called Khuzestan. The frontier runs by the Shatt-ol Arab which is formed by the junction of the Tigris and the Euphrates. Thanks to the extensive irrigation, not only cereals, but more profitable crops such as cotton, rice and sugar-cane now are grown there on a large scale. Ahvaz the capital of Khuzestan, is situated in the heart of the plain and is extremely hot most of the year. The town of Shushtar is on the right bank of the river Gargar, flanked by Dezful in the west, and by Ahvaz and the Qir Dam in the south. Shuslitar was an important site under the Parthian and Sassanian, as confirmed by the considerable number of bridges and fire temples remaining. The town's ancient water mills are among its attractions.

About 85 km. from Ahvaz a road on the left leads to the site of Susa (Shus). What is now just sand and desert - with some ancient remains brought to light by the excavators - used to be one of the most flourishing and most ancient cities of Iran. The ruins of Susa spread over four hills the tell of the Acropolis -the royal city of the Elarnites -, the tell of the Apadana - the site of the palace of Darius I -, the tell of the Royal town - used to be occupied by the residential districts for countries and officials -, and the tell of the craftsman's town (containing two different types of tombs). In the ruins of a 7th century B.C. village on the banks of the Chahour is the so-called tomb of the prophet Daniel, which is greatly venerated by the Shiites. 45 km. south-east of Susa is Chogha Zanbil, a huge Ziggurat or artificial mound constructed by king Huban Untash at the city of Dur Untash about 1250 B.C. The king wanted to make this city the most important of pilgrimage in his realm:

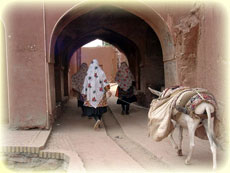

Kashan lies 251 kin. from the capital on the edge of the central desert. We should note that the civilization of Sialk, dating back to some 5000 years ago, flourished for some 3000 years near present-day Kashan. It has a number of popular historic sights, namely the Aqa Bozorg Mosque, the Madrasah-ye Soltan, the princely gardens of Fin. Two of the most famous are the Tabatabaei and Boroujerdi residences, with attractive plasterwork and painted decorations. The town of Natanz south of Kashan has an interesting 14th century mosque, as well as the mausoleum of Sheikh Abd-ol Samad located inside a former monastery (Khaneqah). Nearby, the village of Abyaneh is famous for its red soil that gives its constructions their fiery hues. Isfahan is at a 414 kin. distance from Tehran. It entered its period of glory when the Safavid monarch Shah Abbas I transferred the capital here from Qazvin, and proceeded to embellish his new capital with palaces and mosques. The Imam (Naqsh-e Jahan) Square is the largest enclosed square in the world. It is surrounded by three great Islamic monuments, namely the Imam Mosque (formerly the "Royal Mosque") the Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque and the Ali Qapu Palace. Isfahan has a considerable number of monuments whose description is beyond the scope of such introductory notes. We just mention the most famous ones such as Chahar Bagh Madrasah, Chehel Sotun Pavilion, the Shaking Minarets, and the Bridges of Shahrestna, Khwaju and See-o Se Pol.

Shiraz is the capital of Fars, and enjoys relatively temperate weather during the year. The l8th century ruler Karim Khan Zand made this his capital. The city is perhaps most famous as the resting place of the great poets Sa'di (died 1291 A.D.) and Hafez (died 1389 A.D.). This is also a city of flowers and of such famous gardens as Afifabad, Eram and Delgosha. Shiraz is also of religious importance, being the resting place of Seyyed Amir Ahmad known as Shah Cheragh, the brother of Imam Reza, the eighth Shiite Imam. One of the most charming residences here is the Qavam residence or Naranjestan, formerly home to the 19th century governor of Fars, Qavam-ol Molk Shirazi.

The province is extremely rich in archaeological remains. Persepolis (Takht-e Jamshid) the ceremonial capital of the ancient Persians is a few miles outside Shiraz. Other important sites are Pasargadae, capital and resting place of the Achaemenian monarch, Cyrus the Great (died 530 B.C.) and Naqsh-e Rostam with the four tombs of the Achaemenian kings.

The province is extremely rich in archaeological remains. Persepolis (Takht-e Jamshid) the ceremonial capital of the ancient Persians is a few miles outside Shiraz. Other important sites are Pasargadae, capital and resting place of the Achaemenian monarch, Cyrus the Great (died 530 B.C.) and Naqsh-e Rostam with the four tombs of the Achaemenian kings.

The province of Yazd, to the east of Isfahan and on the western fringe of the great Lut desert, is some 667 km. from Tehran. Marco Polo visited Yazd on his way to China and called it the cc good and noble city of "Yazd". The town's hot desert climate has given rise to great many water cisterns and wind towers. The town presents ideal examples of desert constructions using mud and straw bricks, and wind towers that are natural air cooling systems. The town's Islamic monuments include the beautifully tiled Jame' mosque, the

11th century Mir Chakhmaq gate and square and the Seyyed Rokn-od Din mausoleum with its turquoise dome.

The province of Kerman is Iran's most southeasterly province after Sistan & Baluchestan. The city of Kerman includes several attractive 19th century sights, including the Bagh-e Shazdeh (Prince's Garden), the Ganjali Khan bath located in the Bazaar. The Ganjali Khan bath is now a museum, with wax figures set up to illustrate how the bath was used. The town of Mahan at a 42-km. distance contains the mausoleum of Shah Ne'matollah Vali, 15th century founder of the Ne'matollahi School of Sufism.

Another local attraction is the town of Barn, 210 km. south of Kerman. This is an area noted for its fruits particularly citrus fruit production. The new town of Bam is next to the old and now deserted, abandoned town. This extensive and set of mud-brick construction was a formidable defensive position in the 17th century.

Further to the southeast the country is only intermittently populated, and the desert encroaches even on some of the towns and villages still established there. These remarks, however, do not apply to Sistan, where Lake Hamun and the Helmand river provide some means of irrigation. Torrid heat regions for many months of the year in Sistan, and a hot wind is said to blow for 120 days.

The 55 km-wide strait of Hormoz is the narrow and crucial stretch of water that links the commerce of the Persian Gulf states to the open seas. The port of Bandar Abbas on the strait has been an important sight since Achaemenian times. Its territory includes the towns of Bandar Abbas, Minab, Bandar Lengeh, Jask and the islands of Qeshm and Abu Musa. The port of Bandar Lengeh (251 km. west of Bandar Abbas) is both hot and humid, with a noticeable population during the summer months.

To the east the Alborz chain forms the mountains of Khorassan, not very high, easy to cross and with exceedingly fertile valleys. Khorassan is Iran's largest province, bordering the states of Turkmenistan and Afghanistan. The most important center in the province is the Shrine of Imam Reza, 8th Imam of the Shiites, in Mashhad. Devotees flock here form all over the country and from abroad. 24 km. west of Mashhad is the town of Tus, wherein is buried Ferdowsi,

2nd century author of the Shahnameh or 'The Book of Kings', and one of Iran's greatest poets.

Semnan is Khorassan western neighbor, a province that is cool and temperate in the north where it reaches the Alborz mountains, and hot in the south on the desert fringe. Its four principal towns are Semnan, Shahrud and Bastam. Bastam has a number of sites including the tomb of the ppet Bayazid-e Bastami, the Kashaneh tower, the 12th century Forumad mosque and the earlier Se1juq mosque.

A special feature of Iran is its diversity, something which is evident in all of the country's aspects. The diversity in geography has given rise to a diversity of vegetation and climate in the different regions of the country, and has made the land rich in produce and almost self-sufficient. There is very little vegetation in the vast desert tracts of the central plateau, except for palm trees round the oases. This is true also of the Persian Gulf area, where palm trees are found. The forests of Mazandaran and Gilan in the north, however, have oak, box tree, fig, alder and ash, while the western mountains and areas in east Khorassan, west Kerman and Fars abound in pistachio, peanut, oak, walnut and maple. Shiraz, the capital of Fars, is of course renowned for the world's most graceful tree, the cypress.

The diversity of the population is quite evident in Iran. It is true that all the Iranians make up one nation, but ethnically speaking there are different groups: the people of Fars, the Baluchis, the Kurds, the Lors, the Mazandaranis, the people of Gilan, the Turks and the Arabs. Each group speaks its own dialect or language, and has its own customs and culture. King Darius enumerates twenty-three different ethnic groups as the peoples of Achaemenian Empire. The list is headed by the Persians and the Medes; then come the people of Khuzestan and those of Armenia and Babylon and 'Parthawa' and Herat and Balkh and Sogdia and Khwarazin and the Saksas.

Long before the Romans dared to venture out of Italy, the Persians under Darius the Great ruled a kingdom that stretched form the Indus to the Nile. Over the centuries, this mighty realm became the prize of many conquerors the Greeks, the Parthians, the Saracens, the Turks, the Mongols, the Afghans. A multitude of races, religions, and civilizations passed over its soil, all leaving indelible imprints, but in the face of these influences, the Persians had the strength not only to survive but also to absorb and adapt the foreign elements while retaining their own customs and traditions.

Long before the Romans dared to venture out of Italy, the Persians under Darius the Great ruled a kingdom that stretched form the Indus to the Nile. Over the centuries, this mighty realm became the prize of many conquerors the Greeks, the Parthians, the Saracens, the Turks, the Mongols, the Afghans. A multitude of races, religions, and civilizations passed over its soil, all leaving indelible imprints, but in the face of these influences, the Persians had the strength not only to survive but also to absorb and adapt the foreign elements while retaining their own customs and traditions.

The third decade of the seventh century was the major turning point in Iranian history, in which the pattern of the country's religious, cultural and psychological development was determined up to the present age. For anyone wanting an insight into modem Iran, the events of this period are extremely important, immensely exciting and still rather mysterious. They were certainly totally unexpected; in 620 when Khosrow Parviz -the Sassanian king- had a twenty-year career of successful conquest behind him, no one could possibly have foreseen that within twenty-five years not merely his dynasty but the whole fabric of Iranian life would have been engulfed and overwhelmed.

During the Sassanian period, Persian architecture underwent major developments in both form and technique. New methods of vaulting, building of domes and constructing iwans came into being which influenced the architecture of both the Byzantine Empire and Islam in the centuries to come. During this period techniques of road-and bridge-building were developed which resulted in some of the most beautiful and enduring bridge forms on the East. In every way the Sassanian period marks an apogee in the history of architecture of this land of turquoise.

This heritage served as the basis upon which the spirit of Islam acted to create the remarkable architecture of Islamic Persia, and architecture which reached a plateau of perfection lasting from the eighth century to the dawn of the modem era. Benefiting from the techniques developed by the Sissanians and the spirit breathed into it by Islamic spirituality, this architecture -evolved into a perfect statement of intelligibility and nobility, of order and harmony, of the wedding of utility and beauty, science and art. From this tradition have flowed such masterpieces as the early mosque of Damghan, the Se1juq and Mongol mosques of Varamin, Na'in and Isfahan, the private houses and bazaars of Kashan, the Gowharshad Mosque of Mashhad and the Sheikh Lotfollah and Royal mosques of Isfahan.

Bridges have been an outstanding feature of Iranian buildings since the earliest times: the dam and bridge attributed to Valerian at Shushtar, Shapur's Bridge at Dezful, the Pol-e Dokhtar and the Pol-e Khosrow between Andimeshk and Khorramabad, all in Khuzestan and the outstanding glories of Iranian bridge-building, the two great work which span the Zayandehrud at Isfahan - the Allah Verdi Khan (1629) and the KhwaJu (1660). These two mighty structures are among the most impressive monuments in Isfahan, and are two of the most remarkable bridges in the world. Along with these remarkable monuments, there are substantial remains of Achaemenian and Sassanian palaces, impressive both in size and in detail, some of which, as at Persepolis, have been almost miraculously preserved. Of Seljuq and Mongol royal residences, however, all traces have disappeared; of the Great Palace at Ghazaniyeh, for instance, not even the foundations are visible. It is only from Safavid times that royal houses have survived intact. A sixteenth-century pavilion still stands in the grounds of the former royal palace at Qazvin. There is a late seventeenth-century kiosk in the lovely royal garden at Fin, above Kashan, in which a few wall paintings of the period have been preserved.

The little palace at Behshahr (Ashraf) on the Caspian dates from the time of Shah Abbas. For practical purposes, Safavid palaces are confined to Isfahan: the Ali Qapu, overlooking the Maidan, which served at once as royal residence and a kind of grandstand for parades and polo matches-, the Chehel Sotun behind it, covering the throne room; and the Talar-e Ashraf, a later and more modest structure in the grounds.

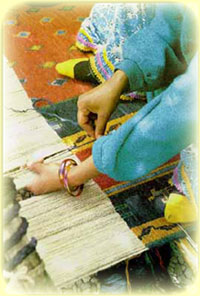

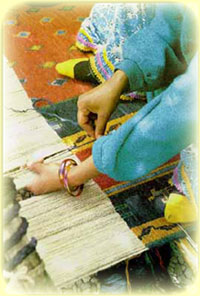

Although the ancient art of Persia came to an end when the Greeks conquered the Achaemeruian empire and brought with them a provincial version of Hellenistic art, which for a time predominated, the great artistic tradition of the past, which had never wholly died out, experienced a revival under the native Sassanian dynasty, which ruled from the fourth to seventh centuries A.D. But conquest of the Sassanian empire by Arabs during the middle of the seventh century temporarily halted the great artistic florescence. However, soon Islamic rulers. Arabs, Se1juq Turks, Mongols, and Turkish Timurids became enthusiastic patrons of Persian craftsmen. Although painting and sculpture disappeared, since the Prophet had forbidden the making of human images, decorative arts again flourished. In fact, ceramics, glass, textiles, and metal work are considered among the best ever-made in Persia, outstanding both for beauty of design and excellence of workmanship.

The last truly creative, and in some ways the most remarkable, period of Persian art was that of the Safavid dynasty, which ruled Iran from 1501 to 1734 A.D. It was during this time that famous Persian carpets were produced at places like Tabriz, Herat, Isfahan, Kashan, and the Caucasus; carpets which have rightly been considered the very epitome of this art form. Ceramics continued to flourish, although they lacked some of the strength and animation of earlier Islamic pottery. And miniature painting, a new art form which had developed under the Mongols, came into full flower and had its golden age under the Timurid and Safavid rulers. Dealing with legends and history of Iran, which they portray in a very sophisticated style, Persian miniatures are a fitting climax to the ancient artistic tradition of Iran, which is one of the oldest and most remarkable in the world.

Archaeology and a wealth of objects which have been excavated from archaeological sites clearly indicate that Iran has always been populated, from the earliest times on, with inhabitants who are endowed with an advanced degree of civilization. Archaeological discoveries tell a tale of gifted and skillful craftsmen whose products traveled far and wide in the markets of the neighboring countries, and this could not have been possible without the, support of a culture and a civilization going back several millennia. This is no place for the presentation of documentary evidence to support such a claim. Suffice it to say that the objects excavated from Susa and Tepe Giyan and Ziwiyeh and Hasanlu and Marlik and Kelardasht, and from Torang Tepe and Shah Tepe and Tepe Hesar in Damghan and the ruins of Ray and the excavations of Sialk, and the artefacts discovered in Qaitariyeh in Tehran and Tal-e Iblis in Kerman and in Tal-e Bakun in Marvdasht and Tal-e Zahhak near Fasa and all the ancient objects discovered 'in natural cave-dwellings and in many other places, all these show a wonderful sense of design and the high level of craftsmanship that has been the characteristic of Persian art throughout the ages.

Archaeology and a wealth of objects which have been excavated from archaeological sites clearly indicate that Iran has always been populated, from the earliest times on, with inhabitants who are endowed with an advanced degree of civilization. Archaeological discoveries tell a tale of gifted and skillful craftsmen whose products traveled far and wide in the markets of the neighboring countries, and this could not have been possible without the, support of a culture and a civilization going back several millennia. This is no place for the presentation of documentary evidence to support such a claim. Suffice it to say that the objects excavated from Susa and Tepe Giyan and Ziwiyeh and Hasanlu and Marlik and Kelardasht, and from Torang Tepe and Shah Tepe and Tepe Hesar in Damghan and the ruins of Ray and the excavations of Sialk, and the artefacts discovered in Qaitariyeh in Tehran and Tal-e Iblis in Kerman and in Tal-e Bakun in Marvdasht and Tal-e Zahhak near Fasa and all the ancient objects discovered 'in natural cave-dwellings and in many other places, all these show a wonderful sense of design and the high level of craftsmanship that has been the characteristic of Persian art throughout the ages.

Culture thankfully rests on more than the visual arts; two pillars of Iranian civilization continue to flourish, language and religion. The modern Persian language, Farsi, is a member of the Indo-European family of languages and, together with most of the tongues of India, belongs to the Aryan or Indo-Iranian branch of the family. This branch has one of the oldest literatures and has been less changed from the reconstructed mother Indo-European language than other members of the family. The two most ancient forms of Iranian language are the Old Persian of the cuneiform inscriptions of the Achaemenians, and Avestan, which is the language of the sacred book of the Zoroastrians. From this ancient stage there is a direct continuity to the Middle Persian languages of the Parthians and Sassanians. Finally we have the modern period of Persian, with remarkably little change in the language, since prose and poetry of the eleventh century A.D. can be understood with ease by any literate Iranian today.

It is hard to get back to the primitive beliefs of the Iranian. For the Avesta is a late compilation. But they seem to have advanced beyond the nature-worship of which traces are preserved in the Gathas, the oldest portion of the Avesta. Many centuries before the Christian era, Zarathustra (Zoroaster) received a revelation from his god Ahura-Mazda, this period saw the birth of "a purified worship, shorn of the blood- sacrifices which still soiled the altars of every Aryan people".

Zoroastrianism or Mazdaism went through changes of fortune. But the Achaemenians, from Darius onwards, and the Sassanians long after supported and protected it, and Ahura Mazda (Hormuzd) held an ever higher place in the Iranian faith. . If he was not the only god, he was the greatest of gods, as the King of Persia was the King of Kings, and effaced the others. He was the sky; he was light; he was symbolized by fire; but he had not, and could not have, an image. His will was for good, and men gained or lost merit according as they observed or disobeyed his law. "All the teaching of Mazdaism tends to produce .... What a beautiful Zend formula calls humaterm, hukhtem, huarestem, 'good thoughts, good words, good deeds" (Yasna, 19, 45). Whatever a man's condition may be - priest, warrior, farmer, or craftsman this condition must be held by a pure man, whose thoughts, works, and deeds are pure. But the role of the Persians in the history of human thought was not confined to the spreading of beliefs of their own. Because they were in relations with so many peoples, and because they treated even the conquered well, they greatly contributed to the syncretic movement which prepared the way for the coming of the universal religions. As early as the Achaemenian epoch, this movement began to develop amply. From the east to the west of the Empire, cults were blended and gods allied. This process became more marked under the Sassanians. Situated in the center of the three great empires of the time, Constantinople, China, and India, the Sassanian Empire was to be for four centuries the point where the human mind exchanged ideas.

From Mazdaism other religions broke off - the worship of Mithra, the doctrine of Mani - which propagated and at the same time contaminated Iranian thought. With the onset of the Safavid dynasty (16th century), Islam became their state religion, which etymologically means surrender and obedience; the surrender of man to the laws governing the Universe and men,

From Mazdaism other religions broke off - the worship of Mithra, the doctrine of Mani - which propagated and at the same time contaminated Iranian thought. With the onset of the Safavid dynasty (16th century), Islam became their state religion, which etymologically means surrender and obedience; the surrender of man to the laws governing the Universe and men,

with the result that through this surrender he worships only the one God and obeys only His commands. The Shiite branch of Islam, refers to those who consider the succession to Mohammad, the Prophet- peace be upon him- to be the special right of the family of the Prophet and who in the field of the Islamic sciences and culture follow the' school of the Household of the Prophet.

In conclusion the history of this vast and diverse land contains numerous pages each one mirroring the life of a nation that has had its brilliant days of glory and grandeur as well as its days of hardship and agony, and that continues its life with vigor and stamina. The roots of the tree of Iranian culture run so deep and are so closely integrated with Iranian soil that no passing storm will ever be able to shake it loose or erase the identity of its people.

National Holidays

The official weekend holiday in Iran is Friday although some public and private sector offices are also closed on Thursdays. The following is a list of public holidays throughout the year . However, it should be noted that the dates on the lunar calendar can not be converted into Christian dates as they change constantly on the solar calendar (See CALENDAR):

Every Friday, the people in Tehran and other Iranian cities perform their Friday prayers ritual. The one held in Tehran at the Tehran University campus is the largest mass of its kind in the region.

Holidays on the Solar Calendar:

- 1-4 Farvardin (March 21-24) Nowruz (New Year)

- 12 Farvardin (April 1) The Islamic Republic Day

- 13 Farvardin (April 2) Late Nowruz holiday

- 14 Khordad (April 4) Imam Khomeini’s demise

- 15 Khordad (April 5) Ann. 1963 uprising

- 22 Bahman (Feb. 11) Islamic Revolution Day

- 29 Esfand (March 20) Nationalization of Iranian

Oil Industry

Days of the Week

There are, of course, 7 days in an Iranian week; however the week begins on Saturday rather than Sunday and thus ends on Friday.

The names of the days in Persian are as follows:

Saturday ~ Shanbeh

Sunday ~ Yekshanbeh Monday ~ Dowshanbeh Tuesday ~ SehshanbehWednesday ~ Chaharshanbeh Thursday ~ Panjshanbeh| Friday ~ Jom’eh | | | | | | |

Friday is always a holiday in Iran, although in some offices there is an extended weekend which covers Thursday too.

Holidays on the Lunar Calendar:

- 9 Moharram Tasua

- 10 Moharram Ashura (Martyrdom of Imam Hossein, AS)

- 20 Safar Arbaeen

- 28 Safar Demise of the holy prophet(SAWA) and Martyrdom of Imam Hassan (AS)

- 17 Rabi-ol-Aval Birth of the holy prophet (SAWA) & Imam Jafar Sadegh (AS)

- 13 Rajab Birth of Imam Ali (AS)

- 27 Rajab Ordainment Day

- 15 Shaban Birth of Imam Mahdi (AJ)

- 21 Ramazan Martyrdom of Imam Ali (AS)

- 1 Shavval Eid-Al-Fitr

- 25 Shavval Martyrdom of Imam Jafar Sadegh (AS)

- 11 Zilqada Birth of Imam Reza (AS)

- 10 Zihajja Eid-Al-Adha

- 18 Zihajja Eid-Al-Ghadir

Please note that the holidays on the lunar calendar have been listed here in the order they were observed in the year 1990-91, corresponding to the solar year 1369 and the lunar Hejirah year of 1410-11.

A brief description around Iran climates

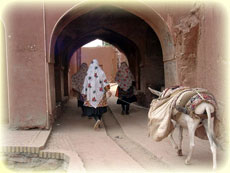

Iran is one of the world's most mountainous countries. Its mountains have helped to shape both the political and the economic history of the country for several centuries. The mountains enclose several broad basins, or plateaus, on which major agricultural and urban settlements are located. Until the twentieth century, when major highways and railroads were constructed through the mountains to connect the population centers, these basins tended to be relatively isolated from one another. Typically, one major town dominated each basin, and there were complex economic relationships between the town and the hundreds of villages that surrounded it. In the higher elevations of the mountains rimming the basins, tribally organized groups practiced transhumance, moving with their herds of sheep and goats between traditionally established summer and winter pastures. There are no major river systems in the country, and historically transportation was by means of caravans that followed routes traversing gaps and passes in the mountains. The mountains also impeded easy access to the Persian Gulf and the Caspian Sea.

Iran is one of the world's most mountainous countries. Its mountains have helped to shape both the political and the economic history of the country for several centuries. The mountains enclose several broad basins, or plateaus, on which major agricultural and urban settlements are located. Until the twentieth century, when major highways and railroads were constructed through the mountains to connect the population centers, these basins tended to be relatively isolated from one another. Typically, one major town dominated each basin, and there were complex economic relationships between the town and the hundreds of villages that surrounded it. In the higher elevations of the mountains rimming the basins, tribally organized groups practiced transhumance, moving with their herds of sheep and goats between traditionally established summer and winter pastures. There are no major river systems in the country, and historically transportation was by means of caravans that followed routes traversing gaps and passes in the mountains. The mountains also impeded easy access to the Persian Gulf and the Caspian Sea.

With an area of 1,648,000 square kilometers, Iran ranks sixteenth in size among the countries of the world. Iran is about one-fifth the size of the continental United States, or slightly larger than the combined area of the contiguous states of California, Arizona, Nevada, Oregon, Washington, and Idaho.

Located in southwestern Asia, Iran shares its entire northern border with the Soviet Union. This border extends for more then 2,000 kilometers, including nearly 650 kilometers of water along the southern shore of the Caspian Sea. Iran's western borders are with Turkey in the north and Iraq in the south, terminating at the Shatt al Arab (which Iranians call the Arvand Rud). The Persian Gulf and Gulf of Oman littorals form the entire 1,770-kilometer southern border. To the east lie Afghanistan on the north and Pakistan on the south. Iran's diagonal distance from

Azerbaijan in the northwest to Baluchestan va Sistan in the southeast is approximately 2,333 kilometers.

Landscape

A series of massive, heavily eroded mountain ranges surround Iran's high interior basin. Most of the country is above 1,500 feet, one-sixth of it over 6,500 high. In sharp contrast are the coastal regions outside the mountain ring. In the north, the 400-mile strip along the Caspian Sea, never more than 70 miles wide and frequently narrowing to 10, falls sharply from the 10,000-foot summit to 90 feet below sea level. In the south, the land drops away from a 2,000 foot plateau, backed by a rugged escarpment three times as high, to meet the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman.

Lakes and Rivers

The Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea, which is the largest landlocked body of water in the world (424,240 sq. km.), lies some 85 feet below the sea level. It is comparatively shallow, and for some centuries has been slowly shrinking in size. Its salt content is considerably less than that of the oceans and though it abounds with fish, its shelly coasts do not offer any good natural harbors, and sudden and violent storms make it dangerous for small boats. The important ports on the Caspian coast are: Bandar Anzali, Noshahr, and Bandar Turkman.

Other Lakes Along the frontier between Iran and Afghanistan there are several marshy lakes which expand and contract according to the season of the year. The largest of these, the Sistan (Hamun-Sabari), in the north of the Sistan & Baluchestan province, is alive with wild fowl.

Real fresh water lakes are exceedingly rare in Iran. There probably are no more than 10 lakes in the whole country, most of them brackish and small in size. The largest are: Lake Urmiya (area: 3,900-6,000 sq. km. depending on season) in Western Azerbaijan, Namak (1,806 sq. km.) in the Central province, Bakhtegan (750 sq. km.) in Fars province, Tasht (442 sq. km.) in Fars province, Moharloo (208 sq. km.) in Fars province, Howz Soltan (106.5 sq. km.) in Central province.

The Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf is the shallow marginal part of the Indian ocean that lies between the Arabian Peninsula and south-east Iran. The sea has an area of 240,000 square kilometers. Its length is 990 kilometers, and its width varies from a maximum of 338 kilometers to a minimum of 55 kilometers in the Strait of Hormuz. It is bordered on the north, north-east and east by Iran, on the north-west by Iraq and Kuwait, on the west and south-west by Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and Qatar, and on the south and south-east by the United Arab Emirates and partly Oman. The term Persian Gulf is often used to refer not only proper to the Persian Gulf but also to its outlets, the Strait of Hormuz and the Gulf of Oman, which open into the Arabian Sea.

Iran consists of rugged, mountainous rims surrounding high interior basins. The main mountain chain is the Zagros Mountains, a series of parallel ridges interspersed with plains that bisect the country from northwest to southeast. Many peaks in the Zagros exceed 3,000 meters above sea level, and in the south-central region of the country there are at least five peaks that are over 4,000 meters. As the Zagros continue into southeastern Iran, the average elevation of the peaks declines dramatically to under 1,500 meters. Rimming the Caspian Sea littoral is another chain of mountains, the narrow but high Alborz Mountains. Volcanic Mount Damavand (5,600 meters), located in the center of the Alborz, is not only the country's highest peak but also the highest mountain on the Eurasian landmass west of the Hindu Kush.

The center of Iran consists of several closed basins that collectively are referred to as the Central Plateau. The average elevation of this plateau is about 900 meters, but several of the mountains that tower over the plateau exceed 3,000 meters. The eastern part of the plateau is covered by two salt deserts, the Dasht-e Kavir and the Dasht-e Lut. Except for some scattered oases, these deserts are uninhabited.

Iran has only two expanses of lowlands: the Khuzestan plain in the southwest and the Caspian Sea coastal plain in the north. The former is a roughly triangular-shaped extension of the Mesopotamia plain and averages about 160 kilometers in width. It extends for about 120 kilometers inland, barely rising a few meters above sea level, then meets abruptly with the first foothills of the Zagros. Much of the Khuzestan plain is covered with marshes. The Caspian plain is both longer and narrower. It extends for some 640 kilometers along the Caspian shore, but its widest point is less than 50 kilometers, while at some places less than 2 kilometers separate the shore from the Alborz foothills. The Persian Gulf coast south of Khuzestan and the Gulf of Oman coast have no real plains because the Zagros in these areas come right down to the shore.

There are no major rivers in the country. Of the small rivers and streams, the only one that is navigable is the Karun, which shallow- draft boats can negotiate from Khorramshahr to Ahvaz, a distance of about 180 kilometers. Several other permanent rivers and streams also drain into the Persian Gulf, while a number of small rivers that originate in the northwestern Zagros or Alborz drain into the Caspian Sea. On the Central Plateau, numerous rivers, most of which have dry beds for the greater part of the year, from snow melting in the mountains during the spring and flow through permanent channels, draining eventually into salt lakes that also tend to dry up during the summer months. There is a permanent salt lake, Lake Uremia (the traditional name, also cited as Lake UROMIEH, to which it has reverted after being called Lake Rezaiyeh under Mohammad Reza Shah), in the northwest, whose brine content is too high to support fish or most other forms of aquatic life. There are also several connected salt lakes along the Iran-Afghanistan border in the province of Baluchestan va Sistan.

SO ,PERSIA has a variable climate. In the northwest, winters are cold with heavy snowfall and subfreezing temperatures during December and January. Spring and fall are relatively mild, while summers are dry and hot. In the south, winters are mild and the summers are very hot, having average daily temperatures in July exceeding 38° C. On the Khuzestan plain, summer heat is accompanied by high humidity.

In general, Iran has an arid climate in which most of the relatively scant annual precipitation falls from October through April. In most of the country, yearly precipitation averages 25 centimeters or less. The major exceptions are the higher mountain valleys of the Zagros and the Caspian coastal plain, where precipitation averages at least 50 centimeters annually. In the western part of the Caspian, rainfall exceeds 100 centimeters annually and is distributed relatively evenly throughout the year. This contrasts with some basins of the Central Plateau that receive ten centimeters or less of precipitation annually.

![]()

Iran is one of the world's most mountainous countries. Its mountains have helped to shape both the political and the economic history of the country for several centuries. The mountains enclose several broad basins, or plateaus, on which major agricultural and urban settlements are located. Until the twentieth century, when major highways and railroads were constructed through the mountains to connect the population centers, these basins tended to be relatively isolated from one another. Typically, one major town dominated each basin, and there were complex economic relationships between the town and the hundreds of villages that surrounded it. In the higher elevations of the mountains rimming the basins, tribally organized groups practiced transhumance, moving with their herds of sheep and goats between traditionally established summer and winter pastures. There are no major river systems in the country, and historically transportation was by means of caravans that followed routes traversing gaps and passes in the mountains. The mountains also impeded easy access to the Persian Gulf and the Caspian Sea.

Iran is one of the world's most mountainous countries. Its mountains have helped to shape both the political and the economic history of the country for several centuries. The mountains enclose several broad basins, or plateaus, on which major agricultural and urban settlements are located. Until the twentieth century, when major highways and railroads were constructed through the mountains to connect the population centers, these basins tended to be relatively isolated from one another. Typically, one major town dominated each basin, and there were complex economic relationships between the town and the hundreds of villages that surrounded it. In the higher elevations of the mountains rimming the basins, tribally organized groups practiced transhumance, moving with their herds of sheep and goats between traditionally established summer and winter pastures. There are no major river systems in the country, and historically transportation was by means of caravans that followed routes traversing gaps and passes in the mountains. The mountains also impeded easy access to the Persian Gulf and the Caspian Sea.

The southern part of the Zagros is called Lorestan. On the slopes of the now denuded mountains once stood green forests of oak, while lower down in the valleys wheat and barley are brown. Because of the heat and drought in the plains, horses and cattle must be driven to the higher pastures of Lorestan in the summer. As a result one part of the population leads a semi nomadic existence which is quite different from that of the people settled in the towns. Part of the Mesopotamian plain to the south-west of the Zagros ranges is called Khuzestan. The frontier runs by the Shatt-ol Arab which is formed by the junction of the Tigris and the Euphrates. Thanks to the extensive irrigation, not only cereals, but more profitable crops such as cotton, rice and sugar-cane now are grown there on a large scale. Ahvaz the capital of Khuzestan, is situated in the heart of the plain and is extremely hot most of the year. The town of Shushtar is on the right bank of the river Gargar, flanked by Dezful in the west, and by Ahvaz and the Qir Dam in the south. Shuslitar was an important site under the Parthian and Sassanian, as confirmed by the considerable number of bridges and fire temples remaining. The town's ancient water mills are among its attractions.

The southern part of the Zagros is called Lorestan. On the slopes of the now denuded mountains once stood green forests of oak, while lower down in the valleys wheat and barley are brown. Because of the heat and drought in the plains, horses and cattle must be driven to the higher pastures of Lorestan in the summer. As a result one part of the population leads a semi nomadic existence which is quite different from that of the people settled in the towns. Part of the Mesopotamian plain to the south-west of the Zagros ranges is called Khuzestan. The frontier runs by the Shatt-ol Arab which is formed by the junction of the Tigris and the Euphrates. Thanks to the extensive irrigation, not only cereals, but more profitable crops such as cotton, rice and sugar-cane now are grown there on a large scale. Ahvaz the capital of Khuzestan, is situated in the heart of the plain and is extremely hot most of the year. The town of Shushtar is on the right bank of the river Gargar, flanked by Dezful in the west, and by Ahvaz and the Qir Dam in the south. Shuslitar was an important site under the Parthian and Sassanian, as confirmed by the considerable number of bridges and fire temples remaining. The town's ancient water mills are among its attractions.

The province is extremely rich in archaeological remains. Persepolis (Takht-e Jamshid) the ceremonial capital of the ancient Persians is a few miles outside Shiraz. Other important sites are Pasargadae, capital and resting place of the Achaemenian monarch, Cyrus the Great (died 530 B.C.) and Naqsh-e Rostam with the four tombs of the Achaemenian kings.

The province is extremely rich in archaeological remains. Persepolis (Takht-e Jamshid) the ceremonial capital of the ancient Persians is a few miles outside Shiraz. Other important sites are Pasargadae, capital and resting place of the Achaemenian monarch, Cyrus the Great (died 530 B.C.) and Naqsh-e Rostam with the four tombs of the Achaemenian kings.

Long before the Romans dared to venture out of Italy, the Persians under Darius the Great ruled a kingdom that stretched form the Indus to the Nile. Over the centuries, this mighty realm became the prize of many conquerors the Greeks, the Parthians, the Saracens, the Turks, the Mongols, the Afghans. A multitude of races, religions, and civilizations passed over its soil, all leaving indelible imprints, but in the face of these influences, the Persians had the strength not only to survive but also to absorb and adapt the foreign elements while retaining their own customs and traditions.

Long before the Romans dared to venture out of Italy, the Persians under Darius the Great ruled a kingdom that stretched form the Indus to the Nile. Over the centuries, this mighty realm became the prize of many conquerors the Greeks, the Parthians, the Saracens, the Turks, the Mongols, the Afghans. A multitude of races, religions, and civilizations passed over its soil, all leaving indelible imprints, but in the face of these influences, the Persians had the strength not only to survive but also to absorb and adapt the foreign elements while retaining their own customs and traditions.

Archaeology and a wealth of objects which have been excavated from archaeological sites clearly indicate that Iran has always been populated, from the earliest times on, with inhabitants who are endowed with an advanced degree of civilization. Archaeological discoveries tell a tale of gifted and skillful craftsmen whose products traveled far and wide in the markets of the neighboring countries, and this could not have been possible without the, support of a culture and a civilization going back several millennia. This is no place for the presentation of documentary evidence to support such a claim. Suffice it to say that the objects excavated from Susa and Tepe Giyan and Ziwiyeh and Hasanlu and Marlik and Kelardasht, and from Torang Tepe and Shah Tepe and Tepe Hesar in Damghan and the ruins of Ray and the excavations of Sialk, and the artefacts discovered in Qaitariyeh in Tehran and Tal-e Iblis in Kerman and in Tal-e Bakun in Marvdasht and Tal-e Zahhak near Fasa and all the ancient objects discovered 'in natural cave-dwellings and in many other places, all these show a wonderful sense of design and the high level of craftsmanship that has been the characteristic of Persian art throughout the ages.

Archaeology and a wealth of objects which have been excavated from archaeological sites clearly indicate that Iran has always been populated, from the earliest times on, with inhabitants who are endowed with an advanced degree of civilization. Archaeological discoveries tell a tale of gifted and skillful craftsmen whose products traveled far and wide in the markets of the neighboring countries, and this could not have been possible without the, support of a culture and a civilization going back several millennia. This is no place for the presentation of documentary evidence to support such a claim. Suffice it to say that the objects excavated from Susa and Tepe Giyan and Ziwiyeh and Hasanlu and Marlik and Kelardasht, and from Torang Tepe and Shah Tepe and Tepe Hesar in Damghan and the ruins of Ray and the excavations of Sialk, and the artefacts discovered in Qaitariyeh in Tehran and Tal-e Iblis in Kerman and in Tal-e Bakun in Marvdasht and Tal-e Zahhak near Fasa and all the ancient objects discovered 'in natural cave-dwellings and in many other places, all these show a wonderful sense of design and the high level of craftsmanship that has been the characteristic of Persian art throughout the ages.

From Mazdaism other religions broke off - the worship of Mithra, the doctrine of Mani - which propagated and at the same time contaminated Iranian thought. With the onset of the Safavid dynasty (16th century), Islam became their state religion, which etymologically means surrender and obedience; the surrender of man to the laws governing the Universe and men,

From Mazdaism other religions broke off - the worship of Mithra, the doctrine of Mani - which propagated and at the same time contaminated Iranian thought. With the onset of the Safavid dynasty (16th century), Islam became their state religion, which etymologically means surrender and obedience; the surrender of man to the laws governing the Universe and men,